An angry undercurrent of frustration with brands

haunts the marketplace.

This, perhaps, has never been more evident than in the recent murder of UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson, shot in the back in midtown Manhattan as he was

walking to an investor conference. A 262-word manifesto found in the possession of the suspect now in custody appears to confirm early speculation that frustration with health insurance coverage was,

at least in part, behind the shooting.

More telling, this act of violence unleashed a torrent of angry, odious vitriol denouncing the health insurance industry. This outpouring of

venomous opinion got to the point that it became front-page news in major media outlets like The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal, sitting alongside breaking coverage of

the manhunt for the killer.

The healthcare industry knows that it is poorly perceived. A recent Gallup poll found only 44% rate healthcare quality as good or excellent, down every

year since 2020 and well below the high this century of 62% in both 2010 and 2012.

Science, too, has taken a hit in recent years. A Pew survey last year found that confidence in

“science” has been steadily declining since 2020 — among both Republicans and Democrats.

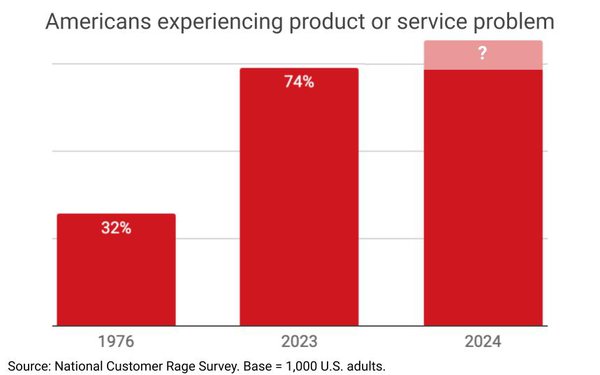

But it’s not just healthcare. For two decades, the National Customer Rage

Study, conducted under the auspices of Arizona State University, has been tracking dissatisfaction with brands and customer service. The most recent survey found 74% of consumers reporting at least

one problem with a product or service during the previous year. This is a record percentage, way more than double the 32% reporting a problem in a 1976 White House survey and nearly double the 39% on

average reporting a problem over the first four waves of this study from 2003 to 2007.

The National Customer Rage Study also finds that 63% of those with a problem became extremely

angry — a.k.a.: enraged — when trying to get the problem resolved. Do the multiplication and it’s almost half of Americans who get pissed off about some product or service every year. By way

of comparison, that same multiplication two decades ago finds just 28% enraged then. Anger is more commonplace than before.

This frustration is about trust. The trust equation is

simple. People trust experts and institutions when they perceive there is an alignment of interests. Which is to say people want to feel reassured and confident that their interests are being advanced

not shortchanged when experts and institutions maximize their interests. Much of the disconnect these days comes from a feeling of misalignment — from the perception that experts and institutions are

pursuing their own interests at the expense of others.

This is certainly what’s in evidence in the anti-health insurance bombasts that have abounded on social media since

Thompson’s murder. “Thoughts and deductibles to the family…Unfortunately my condolences are out-of-network,” read one particularly hateful comment in a CNN thread.

This is a difficult situation for brands. In the strategic choice between value-add and value-out, brands are often forced into the latter. During the worst of the post-pandemic inflationary

spike, many FMCG brands had to engage in shrinkflation to hold unit prices. Private equity owners often saddle portfolio companies with so much debt that brands have no choice but to reduce

the quality and scope of their offerings in order to stay afloat. In the natural progression of greater cost-efficiencies, companies have turned more and more to outsourcing and tech-assisted DIY

options for customer service, which has seeded untold numbers of memes about wasted time and unresolved problems.

While technology has improved many points of interaction between

brands and consumers, it has also created more ways to annoy, frustrate and anger people. The more technology is applied, the more risks that emerge. For example, with social media now used as a

customer service platform, consumers are newly at risk from imposters posing as online service agents who then steal information and money.

And not just social media. It’s the

whole array of things that can create frustration and annoyance, whether IVR (interactive voice responder) or chatbots or outsourcing. Not to mention data breaches and hackers.

The

biggest challenge for brands, though, is other brands, which can poison the waters for all. People angered by one brand often carry over that foul mood and mistrust to every brand. Sullen customers

are more likely to act out no matter what a brand does. Indeed, it is often the case that some small glitch with a brand is the proverbial last straw. It’s not the brand in that moment —

it’s everything else leading up to that moment, especially other brands. Increasingly, this is the consumer that brands encounter, which is difficult and costly.

It’s

discouraging to realize that incivility is the backdrop of life nowadays. But that is the situation in which people find themselves. The litany of incivility is long and onerous. Road rage shooting

and mass shootings are up. Hate crime incidents and school bomb threats are up. Unruly airline passenger incidents and speeding-related auto fatalities are up. Swearing at work is up. So, too, being

treated rudely by work colleagues. Obviously, this is not everyone. But it’s the context within which everyone must navigate their daily lives. And it keeps people on edge. To say it again, this

is the consumer that brands encounter.

Brands have always been a positive, uplifting influence in culture and society. The best advertising is aspirational. The best products improve

lives. The best entertainments enrich the world.

Making things better by solving problems is the very essence of marketing. It’s needed more than ever. We’ve just gotten

another wake-up call about it. Time now to recommit our brands to pleasing people, not pissing people off even more.