A recent Ahrefs blog post claimed that Google is “stealing” international search traffic by automatically translating foreign-language content and serving it through its own infrastructure, bypassing the original publisher’s site.

This bold accusation sparked debate across the SEO and publishing communities. The implications are serious. But as with most things involving Google, the reality is more nuanced.

The headline “Google Is Stealing Your International Search Traffic With Automated Translations” is designed to provoke. The word “stealing” implies intentional wrongdoing, and the certainty of “is” makes it sound like a settled fact, asserting that Google is actively engaging in unethical behavior.

That kind of language goes beyond clickbait and risks crossing into defamation, especially given that the article later concedes this only occurs when no high-quality local-language content is available.

A closer look reveals a more complex picture.

Yes, Google is surfacing machine-translated content in some markets, but typically only when localized pages aren’t available or don’t meet quality thresholds.

The real concern is publisher disintermediation: users receiving the answer without ever reaching the original site. But based on our testing, the actual impact varies significantly by browser, device, and geography.

In many cases, especially for users on Chrome, searchers are routed directly to the publisher’s site, where Google’s in-browser translation handles localization. No proxy. No loss of attribution.

In contrast, Safari and Firefox users are far more likely to trigger Google’s translation proxy (translate.goog), keeping the experience within Google’s ecosystem and away from the publisher’s site.

This browser-level divergence, along with regional language gaps, means the problem needs to be viewed through two distinct lenses:

- What users see in the SERP.

- What happens when they click.

Without controlled testing across browsers, markets, and devices, it’s premature to claim this is a uniform or systemic threat.

That said, there are strategic opportunities here.

Publishers can start by identifying which of their pages are appearing in AI Overviews with translated URLs (as Ahrefs recommends) and cross-referencing that with browser usage data in their analytics. This provides a clearer picture of exposure – and a roadmap for localization investment.

In short, the disintermediation risk is real but fragmented. Context matters, and with the right insights, publishers can act rather than just react.

The following sections illuminate the problem’s mechanics, the nuances of what Google may actually be doing, and some key elements of the Ahrefs article that, while directionally valid, may overstate or mischaracterize the situation.

What does the article claim?

The primary claim is this: Google is showing machine-translated versions of English-language content directly in search results, hosted on a Google proxy domain, bypassing the original publisher’s site.

As a result:

- Publishers lose referral traffic, user behavior, and engagement data.

- Google maintains control of the user experience and monetization pathways.

This understandably feels like disintermediation.

What did Google actually say?

The most important (and often overlooked) line in Google’s explanation is this:

- “This only happens when our systems determine that there is no high-quality, local-language content available for the user’s query.”

That qualifier matters. This isn’t a broad replacement strategy – it’s a fallback mechanism when there’s a content gap in a user’s language.

What is Google actually doing with translation proxies?

Google has quietly rolled out a translation proxy system that activates when someone searches in a language without high-quality local results.

This isn’t like manually using Google Translate or a browser pop-up. It’s a server-side translation triggered by Google that is invisible to the publisher.

Instead of sending users to the actual website, a proxy delivers a machine-translated version of the page on a Google-controlled subdomain using the original content domain set as a subdomain on translate.goog.

For example, www-searchengineland-com.translate.goog. Google shows this version in AI search results, sometimes labeled “Translated by Google.” The user stays entirely within Google’s environment, not the publisher’s site.

As a result:

- The publisher loses traffic, analytics, retargeting, and monetization.

- To the searcher, the content looks like it comes from the source, but Google is serving it.

- Publishers may not even know their content is being shown this way.

While the goal is to help users get information in their language, it raises serious concerns about control, visibility, and fair value exchange for content creators.

What did we find?

Replicating what Ahrefs and others reported turned out to be more complicated and more revealing than expected.

We established a controlled test environment that mimicked a local user: adjusting browser language preferences (Chrome, Firefox, Safari), setting Google’s search interface and region to the target market, and using VPNs to simulate local IP addresses.

Through this process, one thing became clear: the publisher disintermediation concern is real but its severity depends heavily on browser type, device, and user configuration.

In our tests, Chrome users were directed to the original publisher’s URL, where Google’s in-browser translation feature activated automatically. This preserved the publisher’s analytics, monetization, and branding.

But in Safari and Firefox, the experience was different. Google’s translation proxy (served via translate.goog) was far more likely to be triggered. And when users land on these proxy pages, every internal link is rewritten to keep them inside that environment. This means users can navigate through the entire site without ever touching the publisher’s actual domain – a major loss in traffic, behavioral data, retargeting capabilities, and potential revenue.

This finding highlights an important reality: browser type is no longer just a UX variable – it’s a business risk. Publishers must begin segmenting traffic by browser to understand their exposure.

Blanket conclusions based on headline numbers can be misleading; real-world impact varies significantly based on the user’s tech stack.

Action 1: Translated SERP snippets in both AI and regular search results

We can confirm that we found multiple queries where Google translated English content to create SERP results for both traditional and AI-generated results.

Our goal was to test whether Google translated content when local content was not available. We did not test the quality of local content vs. English content. For our testing, we used a variety of Spanish, Indonesian, Thai, and Turkish queries.

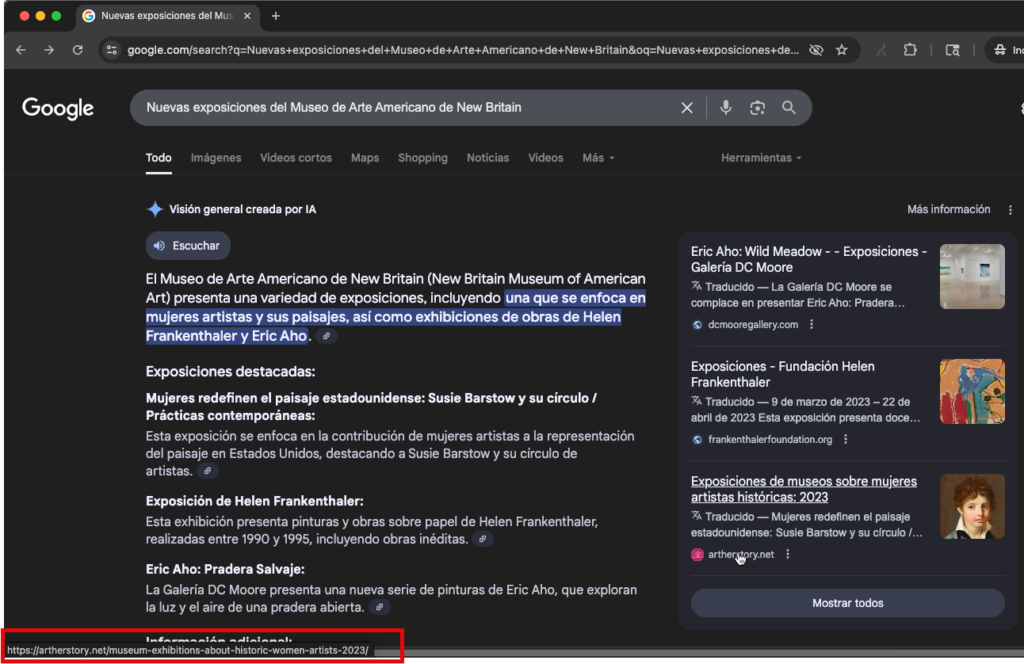

For the example below, we used a Spanish-language query, searching in Mexico to learn what Google would present when asking about new art exhibits at our local museum. We assumed there should not be local content and that Google would require translation for a response.

Chrome experience

A Chrome search in Google returns multiple AI-generated results that have been auto-translated along with a robust AI Overview block of information.

Mousing over the link to the Website in the AI results, the URL is for the publisher’s website and is not injecting a Google Translate URL.

Safari experience

A Safari search in Google returns one AI-generated result that has been auto-translated.

Mousing over the link to the website in the AI results, we could see the Google Translate URL followed by the website page, a set of parameters to trigger the translation system. The string also contained an instruction to open a new tab to present the results keeping the SERP page in the original tab.

- hl=es is the Interface Language – sets Google Translate to Spanish based on my language browser language preference.

- sl=en is the source language of the content. This can also be sl=auto

- tl=es is the target language for translation.

- client=sge indicates the result was in sge

Firefox experience

A search using Firefox in Google returns AI results and two call-outs, both auto-translated.

Mousing over the link to the website in the AI results, we could see the Google Translate URL followed by the website page and a set of parameters similar to Safari. Unlike Safari, it did not include an instruction to open a new tab to present the results.

Action 2 – On click action

We saw different actions depending on the browser used. In every test using Chrome, we were taken to the publisher’s site, and Chrome triggered the page’s translate feature. The only anomaly was that if we opened the URL in a new window, this did not trigger translation.

Chrome experience

On click, we are taken to the publisher’s webpage. The Chrome browser translation function immediately kicks in, translating the website and rendering the Google Translation toggle option.

This pattern held true across all Chrome tests: when the publisher’s URL was shown in the snippet, the click led directly to their site, not to a translate.goog or translate.google.com proxy. With our limited tests, it appears that no publisher disintermediation occurred when SERPs were clicked using a current Chrome browser.

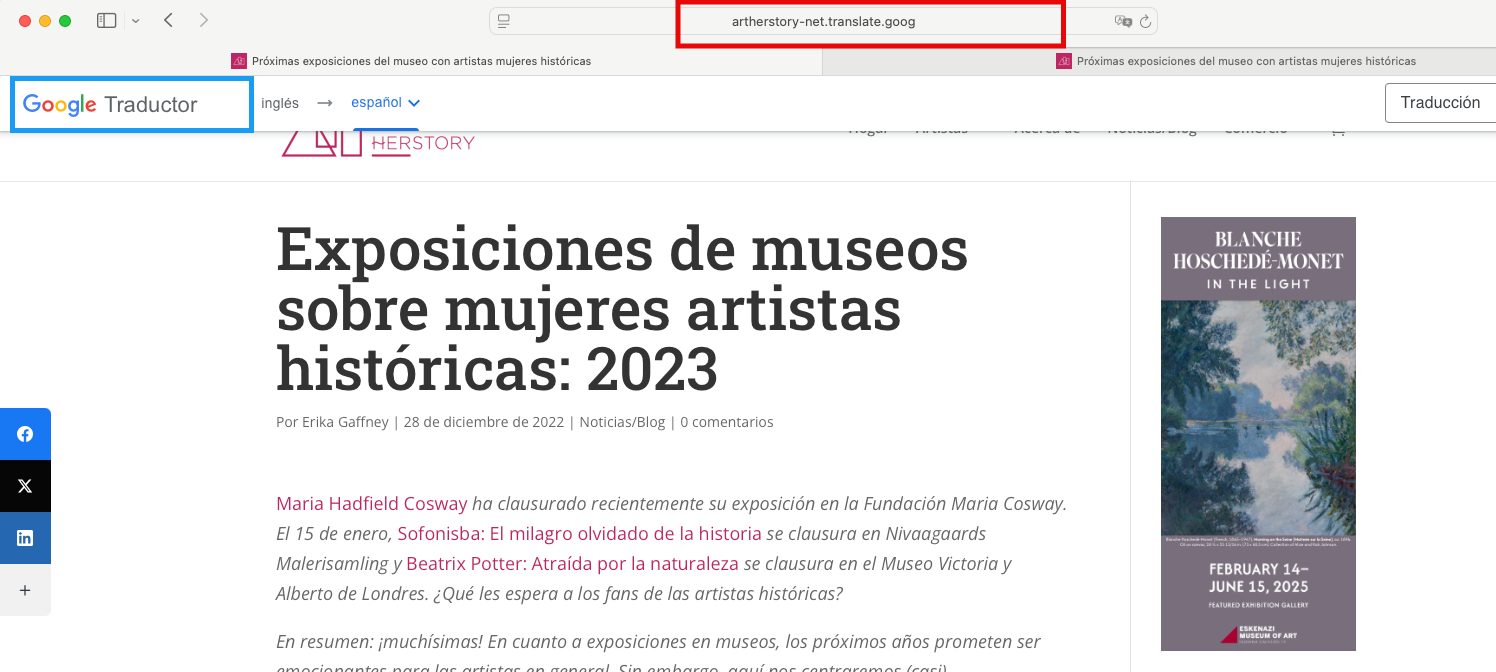

Safari experience

On click, the URL triggers a new tab for Google Translate, which is clearly labeled in the screen capture. Notice that the address bar for the new tab is for the Google Translation Proxy service artherstory-net.translate.goog and not the publisher’s website.

https://artherstory-net.translate.goog/museum-exhibitions-about-historic-women-artists-2023/?_x_tr_sl=en&_x_tr_tl=es&_x_tr_hl=es&_x_tr_pto=sge

The parameter at the end is similar to Google Translate instructions.

- x_tr_sl=en&_x_tr_tl=es&_x_tr_hl=es&_x_tr_pto=sge

- x_tr_sl=en – is the source page language

- x_tr_tl=es – is the target language for translation

- x_tr_hl=es – is the Interface Language

- x_tr_pto=sge indicates the proxy translation origin as SGE

Clicking links on the translated page spawned the same action of calling the publisher’s page into Google Translate, essentially creating a gated environment by keeping the user in the Google proxy translation system.

Firefox Experience

On click, the Firefox browser has the same response as Safari. A click on the URL triggers a new tab for Google Translate, which is clearly labeled in the screen capture.

Notice that the address bar for the new tab is for the Google Translation Proxy service artherstory-net.translate.goog and not the publisher’s website. The full URL path is: https://artherstory-net.translate.goog/museum-exhibitions-about-historic-women-artists-2023/?_x_tr_sl=en&_x_tr_tl=es&_x_tr_hl=es&_x_tr_pto=sge

Publisher recommendations

- Review the amount of traffic from Safari and Firefox browsers and older versions of Chrome that are not triggering auto-translation when the content differs from the searcher’s browser language preference.

- The local content quality variable may offer opportunities for publishers interested in targeting markets that lack quality local content in your vertical.

Interesting finding:

We struggled to replicate Erik’s query about the Spanish term for [respiratory system]. It didn’t make sense that Google would need to use translated content in Spain – and it turns out it doesn’t. Our tests only saw local Spanish websites in the AI Overview and top search results.

Then we noticed Erik had used a SERP simulator set to ES-419, which is Spanish for Latin America, not Spain. When we switched our VPN to countries like Bolivia, Peru, and the Dominican Republic, we saw the same translation-triggered results he did. But we didn’t see them in Mexico or Argentina, where there seems to be more robust Spanish medical content.

This suggests that Google’s translation proxy is not just language-based but also considers content quality at the country level.

Why is Google using its domain (translate.goog) instead of the publisher’s?

Control, consistency, and risk mitigation drive this deliberate technical choice.

Logically, Google would use its domain to serve proxy-translated content because it gives them full technical control, avoids compatibility and legal issues and ensures translation consistency.

It’s not just a UX decision; it’s a strategic infrastructure move to operate translation as a contained system, separate from the publisher’s environment. Using translate.goog gives Google:

- Technical autonomy to ensure consistent rendering, translation accuracy, and performance.

- Legal clarity by separating Google’s machine-translated version from the publisher’s official content.

- Experience consistency across devices, browsers, and content types – without relying on or interfering with the publisher’s code.

As outlined in our alternatives section, this approach may not be perfect for publishers, but it’s the only scalable method that balances user access with engineering and legal realities.

- As a tongue-in-cheek aside, maybe the next evolution is Translate.goog Pro

, a paid proxy service where Google agrees to pass traffic, analytics, and first-party data back to the publisher for a fee. After all, if user engagement is happening on Google’s infrastructure, publishers may purchase their data in true platform-as-a-service fashion.

, a paid proxy service where Google agrees to pass traffic, analytics, and first-party data back to the publisher for a fee. After all, if user engagement is happening on Google’s infrastructure, publishers may purchase their data in true platform-as-a-service fashion.

Was this a classic example of a product built for scale and compliance?

I wonder if this is a bug similar to the AI Mode rollout, where Google unintentionally added the rel=”noopener” attribute to outbound links.

The AI Mode tracking issue was a confirmed bug, an unintentional consequence of how links were coded, which Google quickly moved to fix.

Appreciating the technical requirements behind Google’s translation proxy, should we assume this is a classic example of a product built for scale and compliance, not for partnership?

The translation proxy setup appears to be an intentional design choice to ensure efficiency, security, and legality, so it’s no surprise that the publisher’s traffic, analytics, and control needs are left out of the equation.

This is more than just a technical oversight; it’s a structural blind spot that will persist in accelerated development cycles and isolates teams that only change when external pressure or new incentives force the issue.

Who is this function for: users or Google profits?

While it’s easy to frame Google’s translation proxy as a profit-driven land grab, the reality is more nuanced.

Yes, Google strengthens its ecosystem by keeping users within its environment and capturing valuable behavioral signals—but it also fulfills a genuine user need: making information instantly accessible across language barriers.

This functionality serves both Google’s interests and the public good. The real tension lies with publishers, who bear the cost of content creation yet may lose attribution, traffic, and data when their work is used in this way. In this light, the proxy isn’t theft, it’s an efficient solution with uneven benefits.

But the practical truth is that users benefit, too. They:

- Get information in their language.

- Don’t need plugins or settings.

- Can access content potentially unavailable to them.

Ultimately, this isn’t simply a matter of whether Google or users benefit more; it’s about how value is distributed in an evolving search landscape.

While publishers understandably feel sidelined by proxy translation, it’s worth asking whether the traffic they’ve “lost” was ever firmly theirs to begin with, primarily when no localized content existed. That said, Google could have taken a more collaborative approach by engaging publishers early, exploring ways to preserve attribution, and supporting sustainable content ecosystems.

Moving forward, the real opportunity lies in creating a more inclusive framework – one where accessibility, transparency, and publisher participation all coexist.

Who are the winners and losers?

Every shift in Google’s behavior creates subtle ripple effects, others seismic. The rollout of auto-translated proxy pages is no different.

While it’s framed as a solution to a user problem with access to information in underserved languages, it inevitably reshapes who benefits, who adapts, and who gets left behind. To understand the full impact, we need to look beyond impressions and ask:

- Who actually gains from this change?

- Who stands to lose?

- Who still has time to flip the script?

Here’s how the winners and losers stack up in the current state of play.

Winners:

- Users: Better access to content in their own language.

- Google: Deeper control over information delivery, user retention.

Conditional winner:

- Publishers who act: Those who localize can replace the proxy with their own content.

Losers (for now):

- Publishers without local content: They lose data, visibility, and control – until they adapt.

What does the publisher lose?

While users gain access and Google strengthens its ecosystem, publishers are left navigating the consequences of being bypassed. This isn’t just a theoretical loss, it has practical implications for revenue, analytics, and long-term strategy.

To understand the real cost, we need to go beyond the abstract and examine precisely what publishers lose when their content is translated and served through Google’s proxy rather than visited directly.

Let’s be specific:

- Traffic: Users stay on Google, not the original site.

- Behavioral data: No engagement metrics like bounce rate, session time, or conversion.

- Retargeting opportunities: You can’t retarget or personalize if you don’t get the visit.

- Monetization: Lost ad revenue or lead gen.

Yes, these losses are real, but they’re also variable. Not all content carries the same intent or value. An informational article may serve its purpose without a click, while a product page or lead-gen asset depends heavily on user engagement.

The challenge for publishers is distinguishing between what traffic is truly valuable and what visibility is simply vanity. And perhaps most importantly, publishers deserve a seat at the table in shaping how their content is used in this new search environment.

Didn’t Google signal this with the release of MUM?

When Google introduced MUM (Multitask Unified Model) back in 2021, one of its most heavily promoted features was its ability to understand and surface information across languages. Google stated explicitly that MUM could:

- “Transfer knowledge across languages, so it can learn from sources not written in the language you searched in.”

At the time, most SEOs and publishers interpreted this as a query understanding enhancement, not a content delivery shift. Interestingly, Olaf Kopp predicted this outcome, yet hoped Google would continue to reward publishers for great content in his 2022 article on MUM and the future of SEO.

As a strategic thinking International SEO, I believed MUM was always about more than semantics. It laid the foundation for what is possible now in AI Mode using Gemini.

- Cross-language answers.

- Translated featured snippets.

- And now, proxy-translated search results.

The proxy translation system isn’t a deviation from MUM’s vision. It is the next logical step.

What are the alternatives?

Before we criticize Google’s decision to serve auto-translated proxy pages, we need to consider the alternative ways it could have addressed the content gap and the tradeoffs each approach brings for users, publishers, and the broader search ecosystem.

Option 1: Prioritize the best local result – even if it’s imperfect

This approach favors showing locally written content in the user’s language, even if it’s less comprehensive than a foreign-language alternative. While it may not consistently deliver the “best” answer in absolute terms, it:

- Reinforces the local content ecosystem.

- Encourages publishers to invest in regional SEO.

- Avoids the need for machine translation or proxy delivery.

The tradeoff is that users may encounter less complete or reliable content, which can lead to frustration if their expectations aren’t met.

Benefits:

- Reinforces the local content ecosystem.

- Encourages investment in regional content creation.

- It avoids the need for proxies or translation overlays.

Disadvantages:

- Local results may be low quality or only partially relevant.

- It could frustrate users expecting more comprehensive answers.

This option aligns more closely with Google’s original vision: surfacing the most relevant local result, not just the most linguistically polished one. But when local content doesn’t exist or doesn’t meet quality thresholds, Google fills the gap itself.

That may feel like disintermediation, but it reveals a market failure. If translated foreign content consistently outperforms local content, the issue isn’t Google’s translation – it’s a lack of investment in discoverable, high-quality content in local languages.

Option 2: Show translated snippet with link to original page

Another alternative is to show a translated snippet in the search results while linking directly to the original page. This seems like a fair compromise and is in sync with AI-generated search results, where Google fulfills the user’s query while still giving publishers a shot at traffic and attribution. But in practice, the effectiveness of this approach hinges on whether users actually click and whether they can engage meaningfully with untranslated content once they do.

- Benefits: Provides attribution and the opportunity for the user to click through to the source. This keeps the user in the publisher’s ecosystem, preserving analytics, monetization, and brand value.

- Disadvantages: Suppose the snippet is too complete (especially in the case of AI-generated answers). In that case, users may not click at all resulting in zero benefit to the publisher despite their content being used.

Follow-on UX risk:

Even if the user clicks through, they may land on a page in a language they don’t understand. In this case, the browser’s built-in translation may or may not activate depending on the browser, settings, or device. This creates a fragmented experience with a high risk of abandonment and the potential for negative brand impact.

Option 3: Show only original language content (e.g., English)

This option allows Google to display the original content in its source language, typically English, regardless of the user’s query language. This avoids the complexity of translation and ensures the most authoritative content is shown. However, it burdens the user to interpret foreign-language content, which can result in a poor experience for non-English speakers and limit access to valuable information.

- Disadvantages: Excludes users who can’t read that language well.

- Impact: Poor user experience, especially for less English-proficient markets.

Each of these alternatives presents a different set of compromises. Prioritizing imperfect local results supports ecosystem growth but risks incomplete answers. Linking to untranslated pages offers attribution but often results in low engagement or a broken experience. Showing original-language content maintains quality but fails users who can’t access it.

Google’s proxy translation system may be imperfect, but it’s a pragmatic response to a structural content gap, not a malicious attempt to bypass publishers.

Option 4 (Hybrid): Localized snippet + user-initiated page translation

Rather than fully proxy-serving translated pages, Google could meet users halfway:

- Display a machine-translated snippet in the local language to improve comprehension and encourage engagement.

- Link to the original publisher’s page directly, not via a proxy.

- Add a clear “Translate this page” button or toggle, allowing the user to activate translation via browser or Google proxy if the browser does not support detection/translation.

This model preserves usability for the user while protecting critical attribution, analytics, and brand experience for the publisher.

Potential Benefits:

- Publishers retain traffic, behavioral signals, and monetization.

- Users still receive helpful, localized cues within the search result.

- Encourages transparency and supports user choice without enforcing a default.

Challenges:

- Requires a modest UI change within the search result experience.

- This may result in fewer translated experiences unless users take action.

- It doesn’t solve for zero-click outcomes in AI Overviews or featured snippets.

Suggested Implementation path:

Google could A/B test this hybrid approach in markets where translation is active via GSC data or utilization of Google Translate and compare:

- Click-through rates to original publisher domains.

- Translation toggle usage.

- Bounce rates and session duration post-visit.

- Publisher sentiment and attribution outcomes.

This hybrid approach isn’t a compromise but an evolution. It maintains the current user experience of the Translate button in the SERPs. It respects the user’s need for accessible information while rebuilding a bridge to the content creators who made that information possible in the first place.

Ultimately, the uncomfortable truth is this:

When local-language content isn’t available or discoverable, Google fills the gap with what it has.

The deeper issue isn’t how Google displays content – it’s why publishers haven’t localized it yet. Any long-term solution must address that root problem, not just the symptoms.

Does it matter what type of content?

The question is multidimensional, and not all content is created or consumed the same way. It may not exist due to low demand for it in the local language.

Whether Google’s proxy translation is a help or a hindrance depends heavily on the intent behind the query and the role that content plays in the user journey. A generic answer to a top-of-funnel question may not require a click, but deeper, action-oriented content often does. That’s where the impact becomes more significant.

- For informational content (e.g., “What is anemia?” or “Best time to visit Kyoto”), the user often wants a quick, accurate answer.

- For interactive content (e.g., product comparisons, calculators, purchase journeys), engagement matters – and being translated but not visited is a problem.

This distinction is critical when assessing whether localization is worth the investment. As we’ll explore later, many of the queries via proxy translation are purely informational, with click-through rates below 2%. In such cases, visibility may not translate into value.

But when engagement, trust, or conversion are the goal, losing the visit means losing the opportunity. Understanding which content types truly need localization can help publishers prioritize their efforts where they matter most.

What needs to change?

If the current system feels unfair, it was never designed with publisher participation in mind. Google is solving a real user problem, but unilaterally, without giving publishers a meaningful role in the solution. That has to change.

To restore balance in the value exchange, we don’t need to stop translation – we need to rethink the framework that governs it. That includes:

- Transparent attribution: Clear, consistent links to original content – even within translated overlays – should be the baseline, not a best-case.

- Data access: Publishers should be able to see when and how their content is used in proxy translation, with visibility into impressions, CTRs, and assisted interactions.

- Participation in the pipeline: Google should offer opt-in or opt-up models where publishers can localize key content or partner in improving machine translations with credit and control.

- Standards for fair use: The industry needs clearer guidelines around the boundaries of fair use, especially as AI and machine translation expand.

This isn’t about halting innovation – it’s about aligning incentives. If publishers are expected to keep producing high-quality content that serves a global audience, they deserve to be recognized, credited, and included in the systems that deliver it.

What’s the best way to report on Google Translation behavior?

In the original Ahrefs article, it’s suggested that you use Ahrefs Site Explorer and filter the Top Pages report for the domain translate.google.com/translate. This approach can reveal Google’s auto-translation behavior triggered by Search Generative Experience (SGE) or translation proxies.

My only caution is that it will reflect where Google has auto-translated content and not necessarily a disintermediation of the publisher so be cautious when using the project’s impacts of this action.

Also note that SGE-triggered translations do not use this domain. They are delivered via Google’s translation proxy infrastructure at .translate.goog, which operates invisibly to users and bypasses publisher analytics entirely.

Independent researchers like Natzir Turrado’s LinkedIn post and Metehan Uzun’s blog post have shown that Google’s proxy translation system uses .translate.goog, not translate.google.com when a user clicks on the link. It also included a includes a distinct query parameter: _x_tr_pto=sge, which indicates that the page was translated as part of Google’s Search Generative Experience.

Natzir’s script https://gist.github.com/natzir/f13e37febb8ba7e5f1e9caed620c26d4 checks for:

- URLs served on .translate.goog.

- The _x_tr_pto=sge parameter in the request string.

If both conditions are met, it redirects the user back to the original publisher’s domain, clearly confirming that the translation was initiated by Google’s AI systems, not the user. The presence of _x_tr_pto=sge and the use of .translate.goog provide hard technical evidence that Google is actively translating and serving publisher content within a proxy environment.

Where do users really land?

The article stated that when Google shows its proxy-translated version in the SERP, the user lands on translate.google.com/translate. We could not replicate this experience.

The translate.google.com/translate URL is only present in the translated SERP for non-Chrome browser users. Chrome users could interact with the actual publisher’s URL.

As we also found, another article clarification, a click to your site by a non-Chrome browser user would go into the Google Proxy environment, the original page translated into their language but served invisibly through Google’s infrastructure creating a scenario where the searcher may never reach the publisher’s website. However, the Chrome user would be taken to the publisher’s website with the visit recorded as Google / organic.

This obfuscation for non-Chrome users minimizes friction and preserves the illusion of a seamless experience, but it also means that publishers lose visibility into the session, attribution, and engagement. The translated experience happens without the publisher or the user fully realizing it.

So, while checking translate.google.com/translate URL strings in the Ahrefs system is an excellent way to identify auto-translated search snippets, it does not capture the complete scope, scale, or nuance of Google’s proxy translations. Relying on it leads to misinterpreting what’s happening under the hood with proxy translations.

Is the size of the problem correct?

The original Ahrefs article flagged substantial risk by identifying 6.2 million AI Overview appearances containing the translate.google.com/translate domain in the snippet URL. They estimated that this could affect up to 377 million clicks.

However, based on our parallel testing, it’s important to put that number in context and avoid overreaction. There are two important caveats:

- These are impressions, not actual clicks. The Ahrefs data counts AI Overview appearances with translated URLs in the SERP, but that doesn’t mean users clicked them, or that they landed on the proxy version.

- The browser in use determines whether the proxy activates. Based on our testing, users on Google Chrome typically land directly on the original page with browser translation enabled. The Google-hosted proxy translation is primarily triggered on non-Chrome browsers like Safari or Firefox.

Real-world example: Brazil

Brazil has the highest number of AI Overview translations: 1.2 million appearances, tied to an estimated 377 million potential clicks. However, browser share data from StatCounter reveals:

- Chrome: 83.38%

- Safari: 5.32%

- Firefox: 1.4%

That means only about 6.7% of Brazilian users will likely experience the Google proxy translation instead of the original site. The risk is much smaller for publishers with a predominantly Chrome-based audience than it appears at first glance. But if your traffic skews toward Safari or Firefox, exposure grows.

Real-world example: Mexico

Mexico, the second-largest market in the dataset, has:

- 1 million AI Overview translations.

- 28.3 million estimated clicks.

- Browser shares: Chrome 83.51%, Safari 9.23%, Firefox 1.11% (StatCounter).

Approximately 2.93 million clicks (10.34%) could be exposed to the proxy translation, nearly double the rate in Brazil. Again, this emphasizes the importance of browser share context when interpreting the impact.

Recommendation:

We strongly advise publishers to review their audience’s browser usage, globally and by key market. If Chrome dominates, the proxy risk is limited. But if your traffic includes a significant share from Safari (especially on mobile or tablet) or Firefox, the likelihood of proxy translation increases.

Also worth noting: Safari’s share of mobile and tablet browsers is significantly higher, with 22.89% of mobile browsers and 33.24% of tablet browsers globally. This deserves deeper testing and segmentation in future analyses.

Open question:

Given the volume of AI Overview results with the translate.google.com/translate URL and that it does not appear when searching with a normal desktop Chrome browser, are SEO SERP and Rank checking tools triggering more proxy translation strings to be presented?

Are rank tracking tools skewing the data?

Two big questions came out of our tests and comparisons to the data. The first was the high number of AI Overview results reported with translate.google.com/translate URLs, and the fact that these URLs rarely appeared in our standard desktop Chrome searches raises an important question:

Could automated rank tracking and SERP monitoring tools trigger more proxy translations than typical user behavior?

Understanding how many rank checkers work, what is the implication of:

- Non-Chrome browser user agents?

- Headless or mobile-first emulation?

- Default language settings that may not match local user preferences?

These factors may artificially inflate the appearance of translated proxy URLs, creating the impression of broader exposure than what Chrome users see. However, this doesn’t mean the risk is overblown. The absolute risk may be underappreciated in mobile-dominant search markets.

Are mobile devices and iOS usage the real exposure layer?

In many countries, mobile search volume far exceeds desktop, and in markets with high iPhone penetration, a significant portion of that mobile traffic runs through Safari by default.

Unless users manually change their browser settings, Safari users are far more likely to trigger Google’s translation proxy experience – especially if a localized version of content doesn’t exist.

In mobile-first and iOS-heavy markets, the disintermediation risk becomes much more real. Publishers may lose traffic, data, and monetization – even if desktop tools suggest minimal exposure.

That’s why analyzing browser share by device type and platform (iOS/Android) is just as important as looking at overall market share.

Why is hreflang added to the narrative?

The article references Patrick Stox’s comment about Google neglecting to improve hreflang, implying that the translation proxy is bypassing it. But that misses the point.

Hreflang only works when localized versions of a page exist. In cases where Google triggers a translation proxy, there was no local-language version. That’s not a failure of hreflang; it’s a failure to localize.

Blaming hreflang and Google’s lack of promised support here is a red herring. The issue isn’t technical misimplementation; it’s content absence.

If a localized page with correct hreflang tags existed, Google likely wouldn’t have intervened. The proxy only activates in a vacuum, not as a workaround to existing hreflang signals.

When did Google ever ‘help creators translate and localize their content?’

The article claims that “instead of continuing to help content creators translate and localize their content, Google has decided to claim the traffic as their own.” But this framing raises a legitimate question:

When has Google ever provided meaningful tools or support to help creators localize content in the first place?

The reality is that, beyond promoting best practices (like hreflang and country targeting), Google has never actively participated in helping publishers translate, review, or manage localized content. There were periods when tools like the Google Translate widget or Translate API were available, but these were deprecated or monetized and not offered as part of a true localization partnership. By the way, these never put the localized output on the user’s site with a crystal clear statement that it cannot and would not be indexed.

So Google’s proxy translations represent a new behavior: not indexing what publishers create but creating a translated experience themselves, hosted on their domain. That’s not a broken promise, it’s a new role Google has assumed, and it changes the rules of engagement.

Is Google being hypocritical with machine-translated content?

On the surface, yes, it appears contradictory. That contradiction doesn’t go unnoticed, and it raises fundamental questions about control, fairness, and the shifting terms of the publisher-platform relationship.

For years, Google warned site owners against using automated translation as low-quality. Pages auto-translated without human review could be seen as thin content or spam and were often devalued. But now, Google is doing just that: auto-translating content and surfacing it in search via its proxy domain, framed as a good user experience without any publisher-side review or involvement.

If you’re being translated, isn’t that a signal?

There’s another side to this. If your content is being shown in another market via translation, that signals demand and lack of competition in that language. This created a significant strategic crossroad that many content teams and international SEO leads now face.

In May 2022, Google released a translated results filter under the Performance report (within the “Search Appearance” filter options of Google Search Console. This enabled site owners a means to:

- See which queries and pages are being served via translation proxies.

- You can measure impressions, clicks, and CTR for these translated appearances.

- You can identify new language-market pairs where your content has untapped potential.

Over the past 90 days, data from the Translated Results filter shows that translated impressions for this website have surged from 10,000 to 22,000 per day.

- A closer look reveals that 60% of this growth comes from Turkish-language queries in Turkey, while 30% comes from Hindi-language searches in India.

- However, 97% of these queries are purely informational, and the overall click-through rate (CTR) is just 2%.

That signals a significant visibility gain but limited engagement. In the context of Google’s growing use of AI-generated summaries and zero-click answers, this raises a critical strategic question: Is this a visibility win, a strategic opportunity, or grounds for a class-action lawsuit against Google?

On the one hand, the impressions of the translated content show that our content is deemed valuable enough to surface even across languages and markets we didn’t intentionally target. That’s a signal of strength regarding authority, relevance, and demand. However, if 98% of users are satisfied without clicking and Google controls the entire interaction through its proxy translation, we’re present but excluded from the user experience. Is that a win? Or is it participation without value?

From a strategic standpoint, it could be a roadmap: the translated results reveal where demand exists and where we might reclaim value through smart localization. But only if we believe those users can be nudged into deeper engagement or conversions – otherwise, we’re simply investing in regaining data Google now withholds.

And yes, this amounts to a systemic appropriation of content without compensation, especially if more of the web begins to see its value captured and rerouted by proxy translations and AI answers. Whether this is a missed opportunity or misuse of power depends on what happens next and whether Google’s role remains that of facilitator or begins to look more like a gatekeeper extracting value without consent.

Where do we go from here?

This is a pivotal moment for international SEO, content strategy, and the evolving relationship between publishers and platforms. Google’s proxy translations may fulfill a user need, but they also reveal a deeper imbalance in the content value chain.

What publishers should do

- Don’t panic – diagnose: If your content is being auto-translated, dig into why, which queries, and from which countries. Use Google Search Console’s translated content filters to uncover patterns and priorities. Go deeper by examining which URLs appear in AI Overviews and whether they’re being served via proxy translation.

- Review your browser exposure: Our testing shows that Chrome users often bypass proxy translation, while Safari and Firefox users are more likely to stay within Google’s translation ecosystem. Audit your site’s traffic by browser and device to assess real disintermediation risk. Markets with high Safari usage may face far greater impact.

- Fill the gap – strategically: Start by localizing top-performing or commercially valuable pages. Proxy translation exposure can serve as a content gap diagnostic tool—don’t just treat it as a threat, use it as an early signal. First movers stand to benefit most.

- Push for attribution and agency: Advocate for clearer, clickable links back to source content—even inside proxy overlays. Encourage Google to add transparency features and publisher controls. For example, an opt-in/opt-out mechanism within Google Search Console for translation proxies could be a meaningful start.

- Focus on the whole experience: Translation ≠ localization. True value comes from engagement—UX, trust signals, cultural alignment, and conversion readiness. Winning the click is just step one. Winning the second click is where publishers regain ground.

Where this must go next

If you’re negotiating content licensing, AI training access, or syndication terms with Google or any platform, translation proxy handling needs to be part of that conversation.

- Who owns the translated output?

- Who gets the traffic, data, or revenue?

This isn’t just a technical issue – it’s a matter of contractual rights and value exchange.

Similarly, this should be a focus of any ongoing or future litigation concerning content use, attribution, and monetization. Proxy translation may be the next flashpoint in defining international fair use and the evolving expectations between platforms and publishers.

The real dilemma: Gaps, missions, and value exchange

At its core, this is a story of gaps – gaps in local-language content, in accessibility, and increasingly, in trust.

Google is addressing a legitimate user need: delivering relevant information in the user’s language when local content is lacking. That aligns with its mission to “organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful.”

But in doing so, Google is disintermediating publishers from their own audiences.

When users remain inside Google’s proxy ecosystem, the original content provider loses visibility, behavioral data, monetization, and attribution. This isn’t classic theft, but it’s not equitable participation, either. The value exchange the internet has been based on is now lopsided.

What’s needed now is not a retreat from Google’s translation but a new model of transparency and collaboration. One where publishers are active partners in closing content gaps, and where platforms like Google don’t just serve content but respect its origin.

Proxy translation may represent a new evolution of search intelligence. But it must also spark a new conversation about what a fair digital ecosystem looks like in a multilingual, AI-assisted world.